Circulatory system

| Circulatory system | |

|---|---|

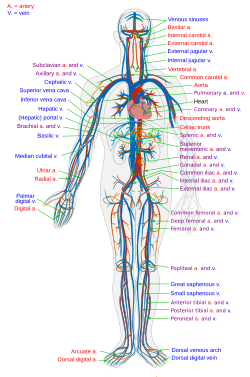

The human circulatory system (simplified). Red indicates oxygenated blood carried in arteries. Blue indicates deoxygenated blood carried in veins. Capillaries join the arteries and veins. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D002319 |

| FMA | 7161 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body.[1][2] It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart and blood vessels (from Greek kardia meaning heart, and Latin vascula meaning vessels). The circulatory system has two divisions, a systemic circulation or circuit, and a pulmonary circulation or circuit.[3] Some sources use the terms cardiovascular system and vascular system interchangeably with circulatory system.[4]

The network of blood vessels are the great vessels of the heart including large elastic arteries, and large veins; other arteries, smaller arterioles, capillaries that join with venules (small veins), and other veins. The circulatory system is closed in vertebrates, which means that the blood never leaves the network of blood vessels. Many invertebrates such as arthropods have an open circulatory system with a heart that pumps a hemolymph which returns via the body cavity rather than via blood vessels. Diploblasts such as sponges and comb jellies lack a circulatory system.

Blood is a fluid consisting of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets; it is circulated around the body carrying oxygen and nutrients to the tissues and collecting and disposing of waste materials. Circulated nutrients include proteins and minerals and other components include hemoglobin, hormones, and gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide. These substances provide nourishment, help the immune system to fight diseases, and help maintain homeostasis by stabilizing temperature and natural pH.

In vertebrates, the lymphatic system is complementary to the circulatory system. The lymphatic system carries excess plasma (filtered from the circulatory system capillaries as interstitial fluid between cells) away from the body tissues via accessory routes that return excess fluid back to blood circulation as lymph.[5] The lymphatic system is a subsystem that is essential for the functioning of the blood circulatory system; without it the blood would become depleted of fluid.

The lymphatic system also works with the immune system.[6] The circulation of lymph takes much longer than that of blood[7] and, unlike the closed (blood) circulatory system, the lymphatic system is an open system. Some sources describe it as a secondary circulatory system.

The circulatory system can be affected by many cardiovascular diseases. Cardiologists are medical professionals which specialise in the heart, and cardiothoracic surgeons specialise in operating on the heart and its surrounding areas. Vascular surgeons focus on disorders of the blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels.

Structure

The circulatory system includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood.[2] The cardiovascular system in all vertebrates, consists of the heart and blood vessels. The circulatory system is further divided into two major circuits – a pulmonary circulation, and a systemic circulation.[8][1][3] The pulmonary circulation is a circuit loop from the right heart taking deoxygenated blood to the lungs where it is oxygenated and returned to the left heart. The systemic circulation is a circuit loop that delivers oxygenated blood from the left heart to the rest of the body, and returns deoxygenated blood back to the right heart via large veins known as the venae cavae. The systemic circulation can also be defined as two parts – a macrocirculation and a microcirculation. An average adult contains five to six quarts (roughly 4.7 to 5.7 liters) of blood, accounting for approximately 7% of their total body weight.[9] Blood consists of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. The digestive system also works with the circulatory system to provide the nutrients the system needs to keep the heart pumping.[10]

Further circulatory routes are associated, such as the coronary circulation to the heart itself, the cerebral circulation to the brain, renal circulation to the kidneys, and bronchial circulation to the bronchi in the lungs. The human circulatory system is closed, meaning that the blood is contained within the vascular network.[11] Nutrients travel through tiny blood vessels of the microcirculation to reach organs.[11] The lymphatic system is an essential subsystem of the circulatory system consisting of a network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, organs, tissues and circulating lymph. This subsystem is an open system.[12] A major function is to carry the lymph, draining and returning interstitial fluid into the lymphatic ducts back to the heart for return to the circulatory system. Another major function is working together with the immune system to provide defense against pathogens.[13]

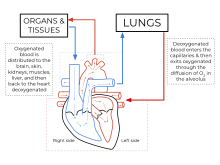

Heart

The heart pumps blood to all parts of the body providing nutrients and oxygen to every cell, and removing waste products. The left heart pumps oxygenated blood returned from the lungs to the rest of the body in the systemic circulation. The right heart pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs in the pulmonary circulation. In the human heart there is one atrium and one ventricle for each circulation, and with both a systemic and a pulmonary circulation there are four chambers in total: left atrium, left ventricle, right atrium and right ventricle. The right atrium is the upper chamber of the right side of the heart. The blood that is returned to the right atrium is deoxygenated (poor in oxygen) and passed into the right ventricle to be pumped through the pulmonary artery to the lungs for re-oxygenation and removal of carbon dioxide. The left atrium receives newly oxygenated blood from the lungs as well as the pulmonary vein which is passed into the strong left ventricle to be pumped through the aorta to the different organs of the body.

Pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is the part of the circulatory system in which oxygen-depleted blood is pumped away from the heart, via the pulmonary artery, to the lungs and returned, oxygenated, to the heart via the pulmonary vein.

Oxygen-deprived blood from the superior and inferior vena cava enters the right atrium of the heart and flows through the tricuspid valve (right atrioventricular valve) into the right ventricle, from which it is then pumped through the pulmonary semilunar valve into the pulmonary artery to the lungs. Gas exchange occurs in the lungs, whereby CO2 is released from the blood, and oxygen is absorbed. The pulmonary vein returns the now oxygen-rich blood to the left atrium.[10]

A separate circuit from the systemic circulation, the bronchial circulation supplies blood to the tissue of the larger airways of the lung.

Systemic circulation

The systemic circulation is a circuit loop that delivers oxygenated blood from the left heart to the rest of the body through the aorta. Deoxygenated blood is returned in the systemic circulation to the right heart via two large veins, the inferior vena cava and superior vena cava, where it is pumped from the right atrium into the pulmonary circulation for oxygenation. The systemic circulation can also be defined as having two parts – a macrocirculation and a microcirculation.[10]

Blood vessels

The blood vessels of the circulatory system are the arteries, veins, and capillaries. The large arteries and veins that take blood to, and away from the heart are known as the great vessels.[14]

Arteries

Oxygenated blood enters the systemic circulation when leaving the left ventricle, via the aortic semilunar valve.[15] The first part of the systemic circulation is the aorta, a massive and thick-walled artery. The aorta arches and gives branches supplying the upper part of the body after passing through the aortic opening of the diaphragm at the level of thoracic ten vertebra, it enters the abdomen.[16] Later, it descends down and supplies branches to abdomen, pelvis, perineum and the lower limbs.[17]

The walls of the aorta are elastic. This elasticity helps to maintain the blood pressure throughout the body.[18] When the aorta receives almost five litres of blood from the heart, it recoils and is responsible for pulsating blood pressure. As the aorta branches into smaller arteries, their elasticity goes on decreasing and their compliance goes on increasing.[18]

Capillaries

Arteries branch into small passages called arterioles and then into the capillaries.[19] The capillaries merge to bring blood into the venous system.[20] The total length of muscle capillaries in a 70 kg human is estimated to be between 9,000 and 19,000 km.[21]

Veins

Capillaries merge into venules, which merge into veins.[22] The venous system feeds into the two major veins: the superior vena cava – which mainly drains tissues above the heart – and the inferior vena cava – which mainly drains tissues below the heart. These two large veins empty into the right atrium of the heart.[23]

Portal veins

The general rule is that arteries from the heart branch out into capillaries, which collect into veins leading back to the heart. Portal veins are a slight exception to this. In humans, the only significant example is the hepatic portal vein which combines from capillaries around the gastrointestinal tract where the blood absorbs the various products of digestion; rather than leading directly back to the heart, the hepatic portal vein branches into a second capillary system in the liver.

Coronary circulation

The heart itself is supplied with oxygen and nutrients through a small "loop" of the systemic circulation and derives very little from the blood contained within the four chambers. The coronary circulation system provides a blood supply to the heart muscle itself. The coronary circulation begins near the origin of the aorta by two coronary arteries: the right coronary artery and the left coronary artery. After nourishing the heart muscle, blood returns through the coronary veins into the coronary sinus and from this one into the right atrium. Backflow of blood through its opening during atrial systole is prevented by the Thebesian valve. The smallest cardiac veins drain directly into the heart chambers.[10]

Cerebral circulation

The brain has a dual blood supply, an anterior and a posterior circulation from arteries at its front and back. The anterior circulation arises from the internal carotid arteries to supply the front of the brain. The posterior circulation arises from the vertebral arteries, to supply the back of the brain and brainstem. The circulation from the front and the back join (anastomise) at the circle of Willis. The neurovascular unit, composed of various cells and vasculature channels within the brain, regulates the flow of blood to activated neurons in order to satisfy their high energy demands.[24]

Renal circulation

The renal circulation is the blood supply to the kidneys, contains many specialized blood vessels and receives around 20% of the cardiac output. It branches from the abdominal aorta and returns blood to the ascending inferior vena cava.

Development

The development of the circulatory system starts with vasculogenesis in the embryo. The human arterial and venous systems develop from different areas in the embryo. The arterial system develops mainly from the aortic arches, six pairs of arches that develop on the upper part of the embryo. The venous system arises from three bilateral veins during weeks 4 – 8 of embryogenesis. Fetal circulation begins within the 8th week of development. Fetal circulation does not include the lungs, which are bypassed via the truncus arteriosus. Before birth the fetus obtains oxygen (and nutrients) from the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord.[25]

Arteries

The human arterial system originates from the aortic arches and from the dorsal aortae starting from week 4 of embryonic life. The first and second aortic arches regress and form only the maxillary arteries and stapedial arteries respectively. The arterial system itself arises from aortic arches 3, 4 and 6 (aortic arch 5 completely regresses).

The dorsal aortae, present on the dorsal side of the embryo, are initially present on both sides of the embryo. They later fuse to form the basis for the aorta itself. Approximately thirty smaller arteries branch from this at the back and sides. These branches form the intercostal arteries, arteries of the arms and legs, lumbar arteries and the lateral sacral arteries. Branches to the sides of the aorta will form the definitive renal, suprarenal and gonadal arteries. Finally, branches at the front of the aorta consist of the vitelline arteries and umbilical arteries. The vitelline arteries form the celiac, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries of the gastrointestinal tract. After birth, the umbilical arteries will form the internal iliac arteries.

Veins

The human venous system develops mainly from the vitelline veins, the umbilical veins and the cardinal veins, all of which empty into the sinus venosus.

Function

About 98.5% of the oxygen in a sample of arterial blood in a healthy human, breathing air at sea-level pressure, is chemically combined with hemoglobin molecules. About 1.5% is physically dissolved in the other blood liquids and not connected to hemoglobin. The hemoglobin molecule is the primary transporter of oxygen in vertebrates.

Clinical significance

Many diseases affect the circulatory system. These include a number of cardiovascular diseases, affecting the heart and blood vessels; hematologic diseases that affect the blood, such as anemia, and lymphatic diseases affecting the lymphatic system. Cardiologists are medical professionals which specialise in the heart, and cardiothoracic surgeons specialise in operating on the heart and its surrounding areas. Vascular surgeons focus on the blood vessels.

Cardiovascular disease

Diseases affecting the cardiovascular system are called cardiovascular disease.

Many of these diseases are called "lifestyle diseases" because they develop over time and are related to a person's exercise habits, diet, whether they smoke, and other lifestyle choices a person makes. Atherosclerosis is the precursor to many of these diseases. It is where small atheromatous plaques build up in the walls of medium and large arteries. This may eventually grow or rupture to occlude the arteries. It is also a risk factor for acute coronary syndromes, which are diseases that are characterised by a sudden deficit of oxygenated blood to the heart tissue. Atherosclerosis is also associated with problems such as aneurysm formation or splitting ("dissection") of arteries.

Another major cardiovascular disease involves the creation of a clot, called a "thrombus". These can originate in veins or arteries. Deep venous thrombosis, which mostly occurs in the legs, is one cause of clots in the veins of the legs, particularly when a person has been stationary for a long time. These clots may embolise, meaning travel to another location in the body. The results of this may include pulmonary embolus, transient ischaemic attacks, or stroke.

Cardiovascular diseases may also be congenital in nature, such as heart defects or persistent fetal circulation, where the circulatory changes that are supposed to happen after birth do not. Not all congenital changes to the circulatory system are associated with diseases, a large number are anatomical variations.

Investigations

The function and health of the circulatory system and its parts are measured in a variety of manual and automated ways. These include simple methods such as those that are part of the cardiovascular examination, including the taking of a person's pulse as an indicator of a person's heart rate, the taking of blood pressure through a sphygmomanometer or the use of a stethoscope to listen to the heart for murmurs which may indicate problems with the heart's valves. An electrocardiogram can also be used to evaluate the way in which electricity is conducted through the heart.

Other more invasive means can also be used. A cannula or catheter inserted into an artery may be used to measure pulse pressure or pulmonary wedge pressures. Angiography, which involves injecting a dye into an artery to visualise an arterial tree, can be used in the heart (coronary angiography) or brain. At the same time as the arteries are visualised, blockages or narrowings may be fixed through the insertion of stents, and active bleeds may be managed by the insertion of coils. An MRI may be used to image arteries, called an MRI angiogram. For evaluation of the blood supply to the lungs a CT pulmonary angiogram may be used. Vascular ultrasonography may be used to investigate vascular diseases affecting the venous system and the arterial system including the diagnosis of stenosis, thrombosis or venous insufficiency. An intravascular ultrasound using a catheter is also an option.

Surgery

There are a number of surgical procedures performed on the circulatory system:

- Coronary artery bypass surgery

- Coronary stent used in angioplasty

- Vascular surgery

- Vein stripping

- Cosmetic procedures

Cardiovascular procedures are more likely to be performed in an inpatient setting than in an ambulatory care setting; in the United States, only 28% of cardiovascular surgeries were performed in the ambulatory care setting.[26]

Other animals

While humans, as well as other vertebrates, have a closed blood circulatory system (meaning that the blood never leaves the network of arteries, veins and capillaries), some invertebrate groups have an open circulatory system containing a heart but limited blood vessels. The most primitive, diploblastic animal phyla lack circulatory systems.

An additional transport system, the lymphatic system, which is only found in animals with a closed blood circulation, is an open system providing an accessory route for excess interstitial fluid to be returned to the blood.[5]

The blood vascular system first appeared probably in an ancestor of the triploblasts over 600 million years ago, overcoming the time-distance constraints of diffusion, while endothelium evolved in an ancestral vertebrate some 540–510 million years ago.[27]

Open circulatory system

In arthropods, the open circulatory system is a system in which a fluid in a cavity called the hemocoel or haemocoel bathes the organs directly with oxygen and nutrients, with there being no distinction between blood and interstitial fluid; this combined fluid is called hemolymph or haemolymph.[28] Muscular movements by the animal during locomotion can facilitate hemolymph movement, but diverting flow from one area to another is limited. When the heart relaxes, blood is drawn back toward the heart through open-ended pores (ostia).

Hemolymph fills all of the interior hemocoel of the body and surrounds all cells. Hemolymph is composed of water, inorganic salts (mostly sodium, chloride, potassium, magnesium, and calcium), and organic compounds (mostly carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids). The primary oxygen transporter molecule is hemocyanin.

There are free-floating cells, the hemocytes, within the hemolymph. They play a role in the arthropod immune system.

Closed circulatory system

The circulatory systems of all vertebrates, as well as of annelids (for example, earthworms) and cephalopods (squids, octopuses and relatives) always keep their circulating blood enclosed within heart chambers or blood vessels and are classified as closed, just as in humans. Still, the systems of fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds show various stages of the evolution of the circulatory system.[29] Closed systems permit blood to be directed to the organs that require it.

In fish, the system has only one circuit, with the blood being pumped through the capillaries of the gills and on to the capillaries of the body tissues. This is known as single cycle circulation. The heart of fish is, therefore, only a single pump (consisting of two chambers).

In amphibians and most reptiles, a double circulatory system is used, but the heart is not always completely separated into two pumps. Amphibians have a three-chambered heart.

In reptiles, the ventricular septum of the heart is incomplete and the pulmonary artery is equipped with a sphincter muscle. This allows a second possible route of blood flow. Instead of blood flowing through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, the sphincter may be contracted to divert this blood flow through the incomplete ventricular septum into the left ventricle and out through the aorta. This means the blood flows from the capillaries to the heart and back to the capillaries instead of to the lungs. This process is useful to ectothermic (cold-blooded) animals in the regulation of their body temperature.

Mammals, birds and crocodilians show complete separation of the heart into two pumps, for a total of four heart chambers; it is thought that the four-chambered heart of birds and crocodilians evolved independently from that of mammals.[30] Double circulatory systems permit blood to be repressurized after returning from the lungs, speeding up delivery of oxygen to tissues.

No circulatory system

Circulatory systems are absent in some animals, including flatworms. Their body cavity has no lining or enclosed fluid. Instead, a muscular pharynx leads to an extensively branched digestive system that facilitates direct diffusion of nutrients to all cells. The flatworm's dorso-ventrally flattened body shape also restricts the distance of any cell from the digestive system or the exterior of the organism. Oxygen can diffuse from the surrounding water into the cells, and carbon dioxide can diffuse out. Consequently, every cell is able to obtain nutrients, water and oxygen without the need of a transport system.

Some animals, such as jellyfish, have more extensive branching from their gastrovascular cavity (which functions as both a place of digestion and a form of circulation), this branching allows for bodily fluids to reach the outer layers, since the digestion begins in the inner layers.

History

The earliest known writings on the circulatory system are found in the Ebers Papyrus (16th century BCE), an ancient Egyptian medical papyrus containing over 700 prescriptions and remedies, both physical and spiritual. In the papyrus, it acknowledges the connection of the heart to the arteries. The Egyptians thought air came in through the mouth and into the lungs and heart. From the heart, the air travelled to every member through the arteries. Although this concept of the circulatory system is only partially correct, it represents one of the earliest accounts of scientific thought.

In the 6th century BCE, the knowledge of circulation of vital fluids through the body was known to the Ayurvedic physician Sushruta in ancient India.[31] He also seems to have possessed knowledge of the arteries, described as 'channels' by Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007).[31] The first major ancient Greek research into the circulatory system was completed by Plato in the Timaeus, who argues that blood circulates around the body in accordance with the general rules that govern the motions of the elements in the body; accordingly, he does not place much importance in the heart itself.[32] The valves of the heart were discovered by a physician of the Hippocratic school around the early 3rd century BC.[33] However, their function was not properly understood then. Because blood pools in the veins after death, arteries look empty. Ancient anatomists assumed they were filled with air and that they were for the transport of air.

The Greek physician, Herophilus, distinguished veins from arteries but thought that the pulse was a property of arteries themselves. Greek anatomist Erasistratus observed that arteries that were cut during life bleed. He ascribed the fact to the phenomenon that air escaping from an artery is replaced with blood that enters between veins and arteries by very small vessels. Thus he apparently postulated capillaries but with reversed flow of blood.[citation needed]

In 2nd-century AD Rome, the Greek physician Galen knew that blood vessels carried blood and identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Growth and energy were derived from venous blood created in the liver from chyle, while arterial blood gave vitality by containing pneuma (air) and originated in the heart. Blood flowed from both creating organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed and there was no return of blood to the heart or liver. The heart did not pump blood around, the heart's motion sucked blood in during diastole and the blood moved by the pulsation of the arteries themselves.

Galen believed that the arterial blood was created by venous blood passing from the left ventricle to the right by passing through 'pores' in the interventricular septum, air passed from the lungs via the pulmonary artery to the left side of the heart. As the arterial blood was created 'sooty' vapors were created and passed to the lungs also via the pulmonary artery to be exhaled.

In 1025, The Canon of Medicine by the Persian physician, Avicenna, "erroneously accepted the Greek notion regarding the existence of a hole in the ventricular septum by which the blood traveled between the ventricles." Despite this, Avicenna "correctly wrote on the cardiac cycles and valvular function", and "had a vision of blood circulation" in his Treatise on Pulse.[34][verification needed] While also refining Galen's erroneous theory of the pulse, Avicenna provided the first correct explanation of pulsation: "Every beat of the pulse comprises two movements and two pauses. Thus, expansion : pause : contraction : pause. [...] The pulse is a movement in the heart and arteries ... which takes the form of alternate expansion and contraction."[35]

In 1242, the Arabian physician, Ibn al-Nafis described the process of pulmonary circulation in greater, more accurate detail than his predecessors, though he believed, as they did, in the notion of vital spirit (pneuma), which he believed was formed in the left ventricle. Ibn al-Nafis stated in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon:

...the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit...

In addition, Ibn al-Nafis had an insight into what would become a larger theory of the capillary circulation. He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (manafidh in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein," a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years.[36] Ibn al-Nafis' theory, however, was confined to blood transit in the lungs and did not extend to the entire body.

Michael Servetus was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation, although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. He firstly described it in the "Manuscript of Paris"[37][38] (near 1546), but this work was never published. And later he published this description, but in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. Only three copies of the book survived but these remained hidden for decades, the rest were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities.

A better known discovery of pulmonary circulation was by Vesalius's successor at Padua, Realdo Colombo, in 1559.

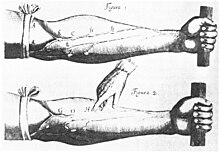

Finally, the English physician William Harvey, a pupil of Hieronymus Fabricius (who had earlier described the valves of the veins without recognizing their function), performed a sequence of experiments and published his Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus in 1628, which "demonstrated that there had to be a direct connection between the venous and arterial systems throughout the body, and not just the lungs. Most importantly, he argued that the beat of the heart produced a continuous circulation of blood through minute connections at the extremities of the body. This is a conceptual leap that was quite different from Ibn al-Nafis' refinement of the anatomy and bloodflow in the heart and lungs."[39] This work, with its essentially correct exposition, slowly convinced the medical world. However, Harvey was not able to identify the capillary system connecting arteries and veins; these were later discovered by Marcello Malpighi in 1661.

See also

- Cardiology – Branch of medicine dealing with the heart

- Cardiovascular drift – medical condition

- Cardiac cycle – Performance of the human heart

- Vital heat

- Cardiac muscle – Muscular tissue of heart in vertebrates

- Major systems of the human body – Collective structure of a human being

- Amato Lusitano – Portuguese physician (1511–1568)

- Vascular resistance – Force from blood vessels that affects blood flow

References

- ^ a b Hall, John E. (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (Twelfth ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 4. ISBN 9781416045748.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 520. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ a b Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 540. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ How does the blood circulatory system work? – InformedHealth.org – NCBI Bookshelf. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. 31 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022.

- ^ a b Sherwood, Lauralee (2011). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems. Cengage Learning. pp. 401–. ISBN 978-1-133-10893-1. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 610. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ "The lymphatic system and cancer | Cancer Research UK". 29 October 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Cardiovascular+System at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Pratt, Rebecca. "Cardiovascular System: Blood". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Guyton, Arthur; Hall, John (2000). Guyton Textbook of Medical Physiology (10 ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-8677-6.

- ^ a b Lawton, Cassie M. (2019). The Human Circulatory System. Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-50-265720-6. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Gartner, Leslie P.; Hiatt, James L. (2010). Concise Histology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-43-773579-6. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walters, P. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 17 August 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Standring, Susan (2016). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (Forty-first ed.). [Philadelphia]: Elsevier Limited. p. 1024. ISBN 9780702052309.

- ^ Iaizzo, Paul A (2015). Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices. Springer. p. 93. ISBN 978-3-31919464-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Iaizzo, Paul A (2015). Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices. Springer. pp. 5, 77. ISBN 978-3-31919464-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Iaizzo, Paul A (2015). Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices. Springer. pp. 5, 41–43. ISBN 978-3-31919464-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b Vaz, Mario; Raj, Toni; Anura, Kurpad (2016). Guyton & Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology – E-Book: A South Asian Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 255. ISBN 978-8-13-124665-8. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ National Institutes of Health. "What Are the Lungs?". nih.gov. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014.

- ^ State University of New York (3 February 2014). "The Circulatory System". suny.edu. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014.

- ^ Poole, David C.; Kano, Yutaka; Koga, Shunsaku; Musch, Timothy I. (March 2021). "August Krogh: Muscle capillary function and oxygen delivery". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 253 (110852). doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.110852. PMC 7867635. PMID 33242636.

- ^ Mcconnell, Thomas H.; Hull, Kerry L. (2020). Human Form, Human Function: Essentials of Anatomy & Physiology, Enhanced Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-28-421805-3. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Parkinson, Clayton Floyd; Huether, Sue E.; McCance, Kathryn L. (2000). Understanding Pathophysiology. Mosby. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-32-300792-4.

- ^ Iadecola, Costantino (27 September 2017). "The Neurovascular Unit Coming of Age: A Journey through Neurovascular Coupling in Health and Disease". Neuron. 96 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030. ISSN 1097-4199. PMC 5657612. PMID 28957666.

- ^ Whitaker, Kent (2001). "Fetal Circulation". Comprehensive Perinatal and Pediatric Respiratory Care. Delmar Thomson Learning. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-7668-1373-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL (17 April 2015). "Surgeries in Hospital-Owned Outpatient Facilities, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief (188). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015.

- ^ Monahan-Earley, R.; Dvorak, A. M.; Aird, W. C. (2013). "Evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and endothelium". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 11 (Suppl 1): 46–66. doi:10.1111/jth.12253. PMC 5378490. PMID 23809110.

- ^ Bailey, Regina. "Circulatory System". biology.about.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Simões-Costa, Marcos S.; Vasconcelos, Michelle; Sampaio, Allysson C.; Cravo, Roberta M.; Linhares, Vania L.; Hochgreb, Tatiana; Yan, Chao Y.I.; Davidson, Brad; Xavier-Neto, José (2005). "The evolutionary origin of cardiac chambers". Developmental Biology. 277 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.026. PMID 15572135.

- ^ "Crocodilian Hearts". National Center for Science Education. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ a b Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci Vol. 49 pp. 243–244, National Informatics Centre (Government of India).

- ^ See Timaeus 77a–81e. For a scholarly discussion, see Douglas R. Campbell, "Irrigating Blood: Plato on the Circulatory System, the Cosmos, and Elemental Motion," Journal of the History of Philosophy 62 (4): 519-541. 2024. See also Francis Cornford, Plato's Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato, Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997.

- ^ The central text here is the Hippocratic text On The Heart, which Elizabeth Craik argues was written between 300 and 250 BC. See Craik, Elizabeth. 2015. The ‘Hippocratic’ Corpus: Content and Context. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Shoja, M.M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Loukas, M.; Khalili, M.; Alakbarli, F.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A. (2009). "Vasovagal syncope in the Canon of Avicenna: The first mention of carotid artery hypersensitivity". International Journal of Cardiology. 134 (3): 297–301. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.02.035. PMID 19332359.

- ^ Hajar, Rachel (1999). "The Greco-Islamic Pulse". Heart Views. 1 (4): 136–140 [138]. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014.

- ^ West, J.B. (2008). "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age". Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (6): 1877–1880. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008. PMC 2612469. PMID 18845773.

- ^ Gonzalez Etxeberria, Patxi (2011) Amor a la verdad, el – vida y obra de Miguel servet [The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus]. Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra. ISBN 84-235-3266-6 pp. 215–228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine Study with graphical proof on the Manuscript of Paris and many other manuscripts and new works by Servetus

- ^ Pormann, Peter E. and Smith, E. Savage (2007) Medieval Islamic medicine Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., p. 48, ISBN 1-58901-161-9.

External links

- Circulatory Pathways in Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax

- The Circulatory System

- Michael Servetus Research Study on the Manuscript of Paris by Servetus (1546 description of the Pulmonary Circulation)